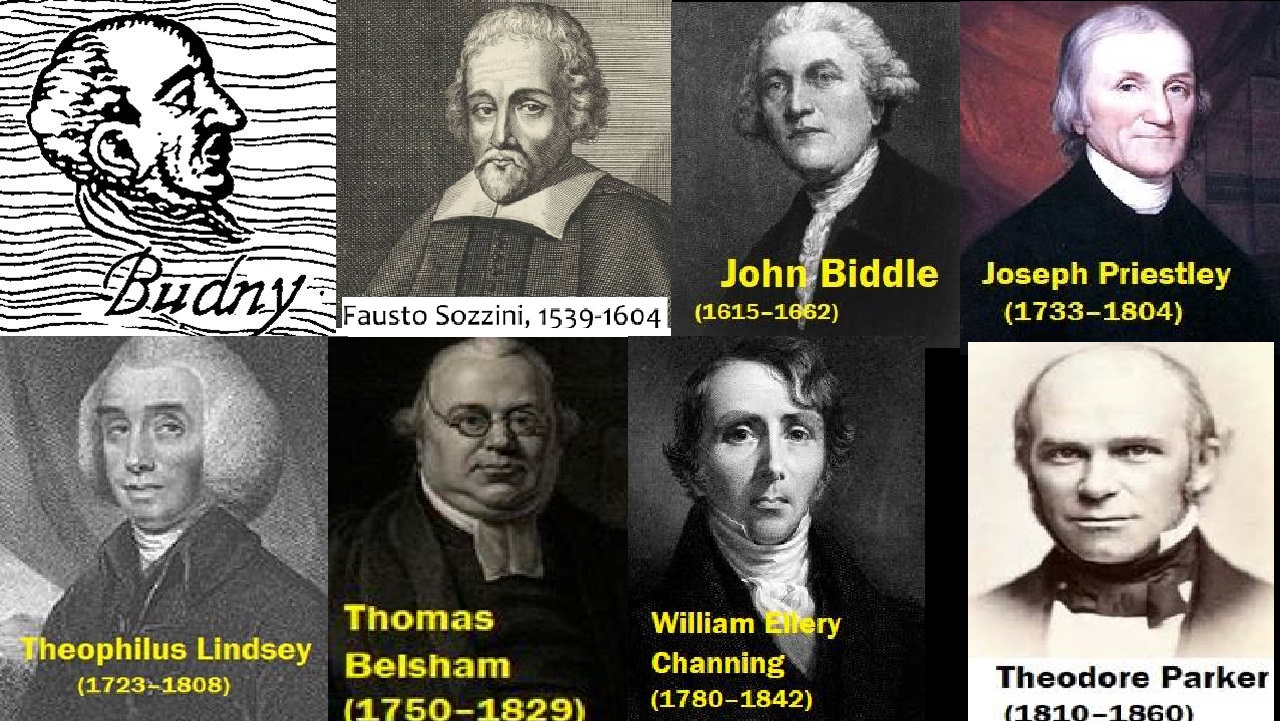

Symon Budny (1530–1593): Polish-Belarusian Unitarian and radical reformer who “denied the Virgin birth, assenting that Jesus was Joseph’s son.” (The Jews in old Poland, 1000-1795 ed. Antony Polonsky, Jakub Basista, Andrzej Link-Lenczowski – 1993 p. 32)

Fausto Sozzini (1539–1604): An Italian theologian and founder of Socinianism (a precursor to modern Unitarianism); On atonement argued that Jesus’ death was not a payment for sin but an example of obedience and a means to inspire human righteousness. See De Jesu Christo Servatore (1578):

“Christ did not die to satisfy divine justice or appease God’s wrath, but to demonstrate the way of righteousness and draw men to repentance by his example.”

As a result, his followers (aka Socinians) emphasized salvation through moral living rather than a sacrificial act, influencing later “polish brethren” aka Biblical Unitarians.

John Biddle (1615–1662): Called the “Father of English Unitarianism,” Biddle saw atonement as a human act of injustice and an example of Jesus’ faithfulness to God’s will. This work is one of Biddle’s most explicit theological statements, where he uses a question-and-answer format to challenge orthodox doctrines, including the idea of Christ’s death as a satisfaction required by God.

1. On Forgiveness as an Act of Divine Grace, Not Payment:

- Question: “How doth God save us by Christ?”

- Answer: “By sending him into the world to make known his will unto us, and to confirm the same by his obedience unto death; whereby he became an example unto us, and a mediator between God and us, that we might be reconciled unto God by him.” (The Scripture Catechism, paraphrase based on surviving editions)

Context: Here, Biddle frames Christ’s death as an act of obedience and mediation, not a payment to satisfy divine justice. He emphasizes reconciliation through Christ’s example and intercession, not a transactional atonement.

- On Christ’s Role and God’s Mercy:

-

Question: “Is not the justice of God satisfied by the death of Christ?”

-

Answer: “The Scripture saith not so; but that God doth forgive sins freely for his own sake, and through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God hath set forth to be a propitiation through faith in his blood.” (The Catechism of the Author, approximate reconstruction from reprints)

-

Biddle directly denies that Christ’s death satisfies God’s justice as a prerequisite for forgiveness. He interprets “propitiation” (e.g., Romans 3:25) as an act of reconciliation or mercy, not a legal satisfaction, and stresses that forgiveness is “freely” given by God.

From Trial Records and Confessions: Biddle’s interrogations, particularly during his 1655 trial for heresy, provide additional insight into his views, as recorded by contemporary sources like parliamentary proceedings or later Unitarian chroniclers (e.g., Joshua Toulmin’s biography).

- Statement During Examination (1655):

-

“I affirm that God can forgive sins without any satisfaction made to his justice, for he is above all law, and his mercy is over all his works; and that Christ died to show forth obedience, and to draw us to God, not to pay a debt that God required.” (Paraphrased from trial accounts cited in Toulmin’s “The Life of Mr. John Biddle”)

-

Context: Under questioning, Biddle explicitly rejects the necessity of Christ’s death as a payment to God, arguing that God’s sovereignty and mercy preclude such a requirement. This aligns with his broader theology that God forgives out of love, not obligation. From “A Confession of Faith Touching the Holy Trinity” (1648). While this work focuses on denying the Trinity, it indirectly addresses atonement by redefining Christ’s role.

2. On Christ’s Mediatory Role: “Christ is that mediator between God and man, not by any satisfaction of God’s justice, which is an imagination of men, but by his obedience and intercession, whereby we are brought nigh unto God.” (Approximate wording based on surviving excerpts)

Biddle dismisses the satisfaction theory as a human invention, instead portraying Christ’s death as part of his obedient service to God, facilitating reconciliation without fulfilling a divine demand.

Notes on Availability and Precision

- Textual Challenges: Many of Biddle’s works were confiscated or burned during his lifetime, and surviving copies (e.g., the 1654 quarto of A Twofold Catechism) are held in rare collections like the British Library or were reprinted later with slight variations. Exact quotes can differ slightly depending on the edition, and some statements are preserved only through summaries by his adversaries or supporters.

- Scriptural Basis: Biddle often cites passages like Micah 7:18 (“Who is a God like unto thee, that pardoneth iniquity… because he delighteth in mercy”) and Hebrews 5:9 (“And being made perfect, he became the author of eternal salvation unto all them that obey him”) to argue that forgiveness is an act of divine mercy and that Christ’s death enables salvation through obedience, not satisfaction.

These quotes and paraphrases collectively demonstrate Biddle’s consistent rejection of the satisfaction theory. He saw Christ’s death as a means of demonstrating God’s love, inspiring human repentance, and mediating reconciliation—distinctly not as a necessary payment to appease God’s justice or wrath. If you’d like, I can dig deeper into a specific text or passage he references, though access to full originals would require institutional archives beyond my current reach! Created by Grok3

Joseph Priestley (1733–1804): A prominent English Unitarian theologian and scientist. He emigrated to the United States in 1794 and helped establish Unitarian congregations, blending nontrinitarian theology with Enlightenment ideals. Universalism, already present in America through leaders like John Murray and Hosea Ballou, grew alongside it. Priestley initially accepted miracles but over time, his rationalist leanings led him to question miracles.

A History of the Corruptions of Christianity (1782)

“The miracles recorded of Christ… ought not to be implicitly received without examination, for many things have been added to the original simple narrative.” Bowers, Joseph Priestley and English Unitarianism in America, 2010 p. 33

“As a result, Priestley spent the remainder of the decade embroiled in a public battle with the Reverend Samuel Horsley … the virgin birth was ascriptural, and the doctrine of the atonement was contrived over centuries of theological errors.”

His work laid the groundwork for a shift away from miraculous interpretations in Unitarian thought.

Theophilus Lindsey (1723–1808): English Unitarian clergyman who founded the first openly Unitarian congregation in London; Lindsey did not hold to vicarious atonement.

A Vindiciae Priestleiana (1788): “The notion that Christ’s death was a propitiation for our sins is a human invention, not supported by the teachings of Jesus himself, who calls us to obedience, not to reliance on a vicarious offering.”

- NOTE His sentiment aligns closely with his theological views, particularly his rejection of traditional Trinitarian doctrines and the concept of Christ’s death as a propitiatory sacrifice, which he considered inconsistent with a rational and benevolent understanding of God. Lindsey’s critique of the idea that Christ’s death served as a propitiation—a means of appeasing God’s wrath—can be inferred from several of his works, where he challenged orthodox interpretations of the atonement. One likely source where this perspective is reflected is his book An Historical View of the State of the Unitarian Doctrine and Worship from the Reformation to our own Times (1783). In this work, Lindsey argues against the traditional Christian doctrines he viewed as human distortions, including the notion of penal substitution or propitiation, favoring instead a Unitarian view that emphasized God’s unity and benevolence over the need for a sacrificial atonement. He saw such ideas as later theological accretions rather than original biblical teachings.

- Another potential source is his The Apology of Theophilus Lindsey: on Resigning the Vicarage of Catterick (1774), where he explains his departure from the Church of England due to his rejection of doctrines like the Trinity and, by extension, related concepts such as Christ’s death as a propitiatory sacrifice. While the precise wording you’ve quoted may not appear verbatim, Lindsey’s broader argument—that many traditional Christian doctrines, including aspects of the atonement, were human inventions rather than divine truths—is consistent throughout his writings.

Thomas Belsham (1750–1829): An English Unitarian minister and successor to Priestley, Belsham explicitly rejected the virgin birth. The Epistles of Paul the Apostle Translated, with an Exposition and Notes (1822)

“The account of the miraculous conception of Jesus is not found in Mark or John, and the passages in Matthew and Luke are of doubtful authenticity, likely introduced to elevate the character of Jesus beyond that of a mere man.”

William Ellery Channing (1780–1842): A leading American Unitarian preacher, Channing focused on the moral teachings of Jesus rather than eschatological promises.

The Moral Argument Against Calvinism (1820) “The Kingdom of God comes not with observation, nor in a future reign of power, but in the silent growth of truth and goodness in the heart.”

Theodore Parker (1810–1860): An American Unitarian minister and Transcendentalist, Parker rejected traditional eschatology, including a literal future Kingdom of God on Earth.

A Discourse of Matters Pertaining to Religion (1842): “The Kingdom of God is not a future event to be awaited with signs and wonders, but a present reality to be built by human hands in love and justice.”

- NOTE the quote might be a modern paraphrase or interpretation of his theological ideas which would align with his broader theology, particularly his rejection of miraculous or supernatural events in favor of moral action. For instance, in his sermon “The Transient and Permanent in Christianity” (delivered May 19, 1841, at the ordination of Rev. Charles C. Shackford in Boston), he argued that true Christianity lies in its ethical teachings and lived experience, not in awaiting future divine intervention. Similarly, in his “Ten Sermons of Religion” (published 1853), particularly the sermon “Of Justice and the Conscience,” he stressed justice as a moral imperative to be enacted by humans in the present, reflecting his belief in a divine order achievable through human effort.