From Word Biblical Commentary on Hebrews 7:18-19

The argument begun in v 11 is brought to a conclusion in vv 18–19. In v 11 the writer deduced from Ps 110:4 that the prophecy of a new priesthood showed the old to be insufficient. In v 12 he implied that a change in the priesthood would necessitate a change in the law by which it was regulated. The subsequent demonstration that Jesus is the eschatological priest acclaimed in Ps 110:4, who holds his office by virtue of a superior qualification, permitted the writer to assert categorically that the old priesthood and law have been replaced by the new arrangement announced in the psalm oracle. The Levitical priesthood and law have been superseded by the new and “better hope” based on the superior quality of the new priest (cf. Cockerill, Melchizedek Christology, 24–25, 113). The climax to the argument is expressed by means of a contrast, introduced by a μέν . . . δέ construction (“on the one hand . . . but on the other,” vv 18, 19b). In all such constructions the emphasis is invariably on the δέ clause (Riggenbach, 200). The writer takes up the notion of the μετάθεσις, “alteration, change,” of the law from v 12, and explains it negatively in v 18 (the “annulment” of the old) and then positively in v 19b (the “introduction” of the new).

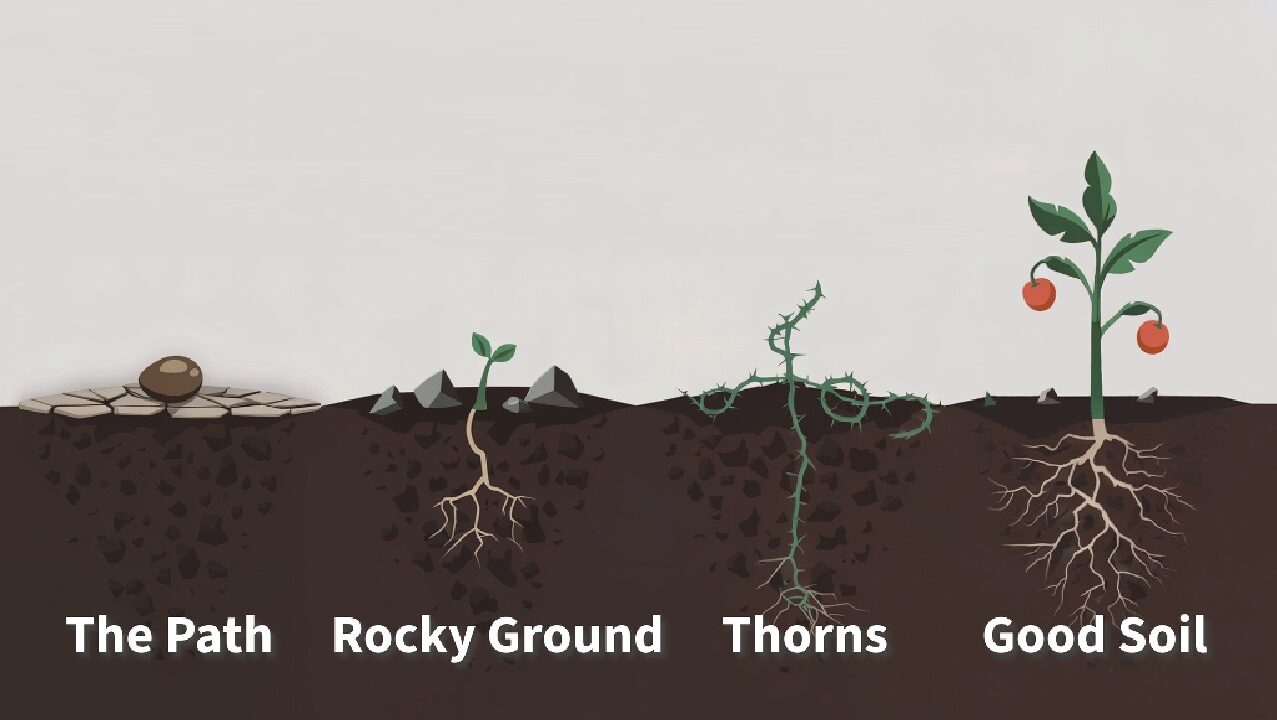

The dramatic change in God’s manner of relating to his people is defined in v 18. The term ἀθέτησις, “annulment,” is a stronger term than μετάθεσις, “alteration” (v 12). Its force is brought out in the papyri, where it assumes a technical legal sense for the annulment of a decree or the cancellation of a debt (MM 12). The use of a legal term in v 18 is appropriate to the argument, which concerns the law. The “former commandment” has primary reference to the particular ordinance regulating the priesthood mentioned in v 16. The writer views the whole OT law under the aspect of the priesthood and sacrifice (cf. Windisch, 66; in Hebrews the law is “the sum of the sacrificial regulations for the ancient cultic community”). The descriptive term προαγούσης, “former, previous in time,” in the expression “former commandment,” is not incidental to the argument. It is in the light of the subsequent eschatological fulfillment that this previous, transitory ordinance based on physical descent has been abrogated. With the promulgation of Ps 110:4, God announced his intention to set aside the whole Levitical system because it had proven to be ineffective in achieving its purpose. Its “weakness” (ἀσθενής) inheres not in the law or its purpose, but in the people upon whom it depends for its accomplishment. Its “uselessness” (ἀνωφελής) derives from the fact that the law regulated the approach to God in a cultic sense and was able to cleanse only externally (9:9–10, 13, 23; 10:14). Both terms are summarized by the sharp parenthetical comment in v 19a, which is translated by Kögel, “nothing was brought to its appointed end” (“Der Begriff,” 60). The finite verb ἐτελείωσεν draws its force from the use of the cognate noun τελείωσις in v 11. The law did not bring the eschatological fulfillment intended by God. The particular concern in v 19a is the failure to bring the people into a right relationship with God through the cleansing of the conscience or heart.

The institutions of priesthood, sacrifice, and atonement were not able to achieve a definitive arrangement of the relationship to God (cf. Riggenbach, 201; Michel, 273; Peterson, “Examination,” 186–87, 220–22). The positive half of the conclusion is drawn in v 19b: although the law proved to be ineffective, it has been replaced by an effective hope. The force of the μὲν . . . δέ construction is to emphasize the initial expressions ἀθέτησις, “annulment,” and ἐπεισαγωγή, “introduction.” A former commandment has been declared invalid: a better hope has been introduced. The word ἐπεισαγωγή is used by Josephus with the idea of replacement (Ant. 11.196: the new wife brought in replaces the old), and this notion seems to be present in v 19b as well. The term κρείττων, “better,” is the characteristic word for the new redemptive arrangement in Hebrews. It signifies the established, certain character of the reality introduced by Christ, which leads the people to the goal appointed by God (Michel, 273). The hope now extended to the people is κρείττων by virtue of its effectiveness, which is guaranteed by God’s fidelity (6:18; 10:23). It concerns what the law and its priesthood had failed to realize and could only point forward to in a symbolic way, namely, direct and lasting access to God. Through this “better hope” the new people of God have secured the assurance of a quality of access to and a relationship with God that were not possible under the Levitical institution.